Thyroid Profile in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study

2Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Kolkata, India

Abstract

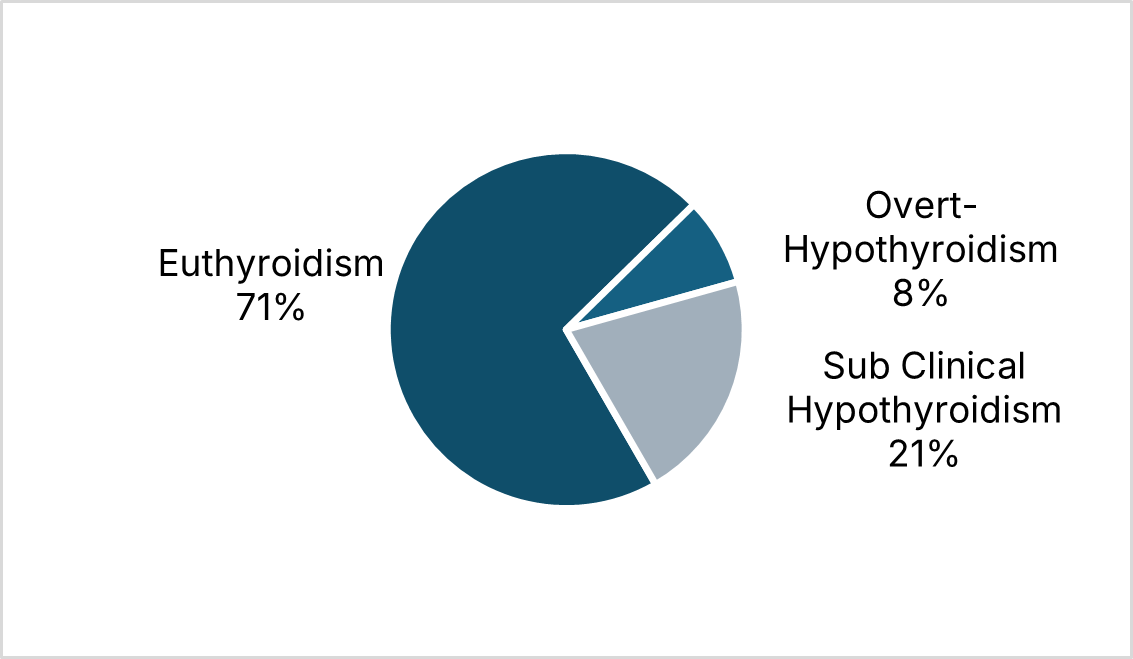

Introduction: Thyroid dysfunction is common in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and may exacerbate morbidity. This study assessed the prevalence of thyroid abnormalities and their association with renal function in CKD patients. Methods: A cross‑sectional study with 100 adults CKD stages 2–5 patients conducted at a tertiary care hospital in Ahmedabad, India (August 2019–September 2021). Thyroid function tests (free T3, free T4, TSH) and serum creatinine levels were measured. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using creatinine clearance. The prevalence of low T3 syndrome and subclinical hypothyroidism was determined. One-way ANOVA, Pearson's correlation, and Tukey post-hoc tests were used to analyse the relationship between thyroid parameters and eGFR. Results: In present study, mean age was 51.8 ± 10.6 years and 74% were male. Low free T3 occurred in 46%, low free T4 in 8%, and elevated TSH in 8% of patients. The prevalence of low T3 increased with CKD severity (stage 3: 4%; stage 4: 35%; stage 5: 57%; p=.007). Free T4 was significantly lower in stages 4 and 5 compared to stage 3 (p=.003). Creatinine clearance is positively correlated with both free T3 (r = 0.262, p=.008) and free T4 (r = 0.306, p =.002). Conclusions: Subclinical hypothyroidism and low T3 syndrome are common in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and are associated with deteriorating renal function. Routine thyroid function screening, including free T3 measurement, is recommended to facilitate timely diagnosis and management, potentially improving clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Chronic Kidney Disease, Thyroid Function Tests, Hypothyroidism

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) includes a spectrum of distinct pathophysiological processes which is associated with abnormal kidney function and a progressive reduction in glomerular filtration rate.[1] CKD has been recognized as a leading public health problem worldwide. The global estimated prevalence of CKD is 13.4% (11.7-15.1%), and patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) needing renal replacement therapy is estimated between 4.902 and 7.083 million.[2]

CKD affects multiple organ systems, including the endocrine system, where thyroid dysfunction is a frequently observed but often underdiagnosed complication.[3] The thyroid and kidneys share a complex interplay, as thyroid hormones play a crucial role in renal physiology, while the kidneys contribute significantly to the metabolism and clearance of thyroid hormones.[4]

Alterations in thyroid function are common in CKD, with hypothyroidism being more prevalent than hyperthyroidism.[5] The most frequently observed abnormality is low triiodothyronine (T3) syndrome, characterized by decreased peripheral conversion of thyroxine (T4) to T3 due to impaired deiodinase activity.[6] This condition, known as sick euthyroid syndrome (SES) or non-thyroidal illness syndrome (NTIS), is often associated with increased inflammation, protein-energy wasting, and poor clinical outcomes.[7] Additionally, CKD patients exhibit reduced T3 and free T4 levels with variable thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) concentrations, often presenting as subclinical or overt hypothyroidism.[5]

The pathophysiology of thyroid dysfunction in CKD involves multiple mechanisms, including reduced renal clearance of iodine, altered thyroid hormone binding to carrier proteins, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and the accumulation of uremic toxins.[4] The kidney plays a key role in iodine elimination, and impaired renal clearance results in increased serum iodine levels, which may contribute to Wolff-Chaikoff effect-induced hypothyroidism.[6] Additionally, the haemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD) processes influence thyroid hormone levels, with a notable prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism among PD patients.[8]

Thyroid dysfunction in CKD has significant clinical implications, contributing to cardiovascular morbidity, metabolic disturbances, and increased mortality.[9] Despite this, thyroid abnormalities in CKD are frequently underdiagnosed due to overlapping symptoms with uraemia and the altered thyroid hormone profile observed in advanced renal disease.[5]

This study aims to determine the prevalence and pattern of thyroid dysfunction among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), and to evaluate the association between thyroid hormone levels (free T3, free T4, TSH) and the severity of renal impairment, as classified by CKD stage and estimated creatinine clearance. A better understanding of thyroid abnormalities in CKD may provide insights into optimizing management strategies and improving patient outcomes.[10]

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study conducted in one of the Tertiary Care Hospital in Ahmedabad, India between August 2019 and September 2021. By using Cochran’s formula (n=4pq/L2), 38.6% prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in CKD patients and 10% of absolute precision, sample size of 100 achieved after rounding up.[4] Patients with chronic renal failure (CRF) were included in the study based on the presence of uremic symptoms persisting for a minimum of three months, elevated blood urea and serum creatinine levels, and reduced creatinine clearance. Ultrasonographic criteria for CRF diagnosis included bilateral contracted kidneys measuring less than 8 cm in both males and females, along with poor corticomedullary differentiation. Additional supportive laboratory findings, such as anaemia, low urine specific gravity, and serum electrolyte abnormalities, as well as radiological evidence of renal osteodystrophy, were considered indicative of CRF. Exclusion criteria encompassed nephrotic-range proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) undergoing renal replacement therapy. Furthermore, individuals with acute illnesses, recent surgery, trauma, burns, or liver diseases were excluded, as were those receiving medications known to affect thyroid function, including amiodarone, steroids, dopamine, phenytoin, beta-blockers, oestrogen-containing contraceptives, and iodine-based drugs.

Bases on inclusion and exclusion criteria 100 cases were selected using purposive sampling. After taking consent, detailed clinical history, general examination, systemic examination, routing haematological, biochemical and radiological investigations (USG abdomen) were recorded. For the thyroid profile, 5 ml of blood sample was collected in nonheparinized serum vacutainer tube and sent to the central laboratory of the hospital. All the data recorded in standard case record form, the entered into Microsoft Excel 2019, and analysed in IBM SPSS 26.0 software.

Results

Present study assessed the thyroid profile of 100 CKD patients. Around 2/3rd of the participants was from the age between 50 to 69 years. Mean age was 51.8 (±10.65) years, around 74% of the participants were males.

| Variables | n |

|---|---|

| Age Group (years) | |

| 30–39 | 15 |

| 40–49 | 21 |

| 50–59 | 32 |

| 60–69 | 32 |

| Free T3 Level | |

| Low T3 | 46 |

| Normal | 54 |

| Free T4 Level | |

| Low T4 | 8 |

| Normal | 92 |

| TSH Level | |

| High | 8 |

| Normal | 92 |

Out of the 100 CKD patients, 56% were in stage 5 of CKD, 31% were in stage 4, 11% were in stage 3 and 1% were in stage 2 and 1 each.

Pearson Correlation of Serum Free T3 (r(98)=0.189, p=.059), Free T4 (r(98)=0.168, p=.095) and TSH (r(98)=-0.216, p=.31) were found statistically insignificant with age. There was a statistically significant difference of free T3 level between groups as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(2,97)=5.295, p=.007). A Tukey post hoc test reveals that the difference of free T3 level in patient with CKD grade 1-3 (1.91 ± 0.46 min, p=.012) was statistically significant with CKD grade 5 (1.53 ± 0.55 min). There was no statistically significant difference of Serum Free T3 level found between CKD grade 4 (p=1) and grade 5 (p=.088) with compared to CKD grade 3. Statistically significant difference of free T4 level between groups as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(2,97)=6.115, p=.003). A Tukey post hoc test reveals that the difference of free T4 level in patient with CKD grade 4 (1.11 ± 0.38 min, p=.023) and Grade 5 (1.04 ± 0.34, p=.002) was statistically significant with CKD grade 3 (1.43 ± 0.38 min). There was no statistically significant difference of Serum Free T4 level found between CKD grade 3 (p=1) with compared to CKD grade 4. There was no significant difference of TSH level between groups as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(2,97)=1.54, p=.220).

| Variable | Free T3 | Free T4 | TSH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 30–39 | 1.59 | 0.43 | 1.01 | 0.40 | 9.75 | 24.79 |

| 40–49 | 1.54 | 0.65 | 0.93 | 0.26 | 4.39 | 5.15 |

| 50–59 | 1.72 | 0.60 | 1.26 | 0.35 | 1.51 | 1.29 |

| 60–69 | 1.84 | 0.63 | 1.13 | 0.40 | 1.90 | 2.83 |

| Grade of CKD | ||||||

| 1–3 | 1.91 | 0.46 | 1.43 | 0.38 | 1.99 | 2.05 |

| 4 | 1.91 | 0.66 | 1.11 | 0.38 | 1.27 | 0.90 |

| 5 | 1.53 | 0.55 | 1.04 | 0.34 | 5.04 | 13.28 |

Creatinine clearance is positively correlated with both free T3 (r = 0.262, p = .008) and free T4 (r = 0.306, p = .002). On the other hand, TSH shows a weak negative correlation with creatinine clearance (r = -0.137) that is not statistically significant (p = 0.173).

Discussion

The present study was conducted in 100 participants to assess the prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in CKD patients and to determine the correlation between thyroid dysfunction and severity of renal disease. Males were predominant (74%) in the study, and maximum participants were from 40 to 60 years.

In present study the mean values of both serum T3 (p=.059) & T4 (p=.095) were significantly low. This is comparable to Ramiraz et al.[11] and Lim VS et al.[12] study. The overall prevalence of low T3 is 46%, in CKD stage 1-3 was 4%, in stage 4 was 35%, and stage 5 was 57%. This observation was consistent with Sang Heon Song et al.[13] in which the prevalence of low T3 will be increased according to the increase in stage of CKD. Low-T3 syndrome has been shown to be the most common thyroid abnormality in a cohort of 279 CKD patients (47%).[14] Furthermore, low T3 syndrome is closely associated with both malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome (MICS) and anaemia, conditions common in CKD.[15]

Low T4 level found in 8 patients, 7 out of 8 patients belonged to either stage 4 or 5 CKD, which was comparable to Fan J. et al.[14], Kaptein et al.[16] and Avasthi G et al.[17] but it was not statistically significant.

The current study shows a positive correlation between free T3 (p=.008) and T4 (p=.002) and creatinine clearance, which was statistically significant and comparable to Khatiwada S et al.[4] study. In another recent cross-sectional study, Rhee et al.[18] assessed thyroid function in 461,607 United States veterans with CKD stages 3–5 and found that every 10 ml/min reduction of Creatinine clearance increased the risk for hypothyroidism. This demonstrate serum T3 levels were associated with severity of CKD even in the normal TSH level.

The TSH values in present study ranged from 0.28-97.5 micro-IU/ml, the mean value being 3.469. High serum TSH level (> 10 µIU/ml) was observed in 8 patients. The prevalence of hypothyroidism in present study is 8%, this is consistent with results of Kaptein et al.[16] All of these patients had very low serum T3 concentration which can be explained by the normal feedback regulation of the pituitary thyroid axis. Four patients had both goitre and pleural effusion. This observation was consistent with Joseph L et al.[19] who studied 175 patients of CKD who had low T3, T4, fT4 but had high TSH levels suggested maintenance of pituitary thyroid axis.

Moreover, multivariate regression analysis showed that Creatinine clearance was a strong independent predictor of serum fT3 levels in patients with Creatinine clearance <60 ml/min. Similar to these results, there is a growing body of evidence supporting the notion that a high prevalence of hypothyroidism (mostly subclinical) is found with CKD progression. Compared to patients with Creatinine clearance >90 ml/min and after adjustment for several factors, low Creatinine clearance was an independent predictor of hypothyroidism with increasing odds ratios according to the progression of CKD.

Out of 70 patients who had normal serum TSH level, 46 patients had low T3 and 8 patients had low free T3 and free T4. So these 46 patients had normal level of serum TSH in spite of low serum T3 level. They demonstrated abnormality in the hypophyseal mechanism of TSH release in uremic patients as the TSH response to TRH was blunted. These results were consistent with study of Spector et al.[20] and Ramirez et al.[11] reported normal level of serum TSH in patients of CKD in spite of low serum T3 levels.

However, when evaluating thyroid function in CKD patients, most clinicians confine their laboratory testing to TSH and do not determine fT3 serum levels. The serum fT3 levels, however, may represent the more accurate assessment of “effective” thyroid status when CKD is prevailing. Another study which was conducted by Joseph L et al[19] and Hardy et al.[21] revealed low T3 T4 level with high TSH level suggesting maintenance of pituitary thyroid axis.

In Joseph L et al.[19] study low FT3, FT3 and TT4 values is seen in clinically euthyroid CKD patients. However, the presence of normal T4 and TSH levels would indicate functional euthyroid status. It can be presumed that free T4 values would fall if these patients’ developed hypothyroidism and TSH values would rise simultaneously. Thus, Free T4 and TSH levels combined can be used for the diagnosis of hypothyroidism in presence of CKD.

In present study no patient was found to have hyperthyroidism. Which was comparable to Gupta et al.[22] study. Ramirez G et al.[11] reported high prevalence of goitre in CKD patients especially those on chronic dialysis. Incidences were increased in end stage renal disease. The possible explanation is the accumulation of iodides in the thyroid gland due to decreased renal clearance in CKD patients. Study conducted by Hegedus et al.[23] showed thyroid gland volume was significantly increased in patients with CKD.

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) affects the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid hormone axis as well as peripheral thyroid hormone metabolism. Among thyroid hormones, T3 is the most metabolically active thyroid hormone and can be reduced in ESRD patients even with a normal TSH level. In general, reduced T3 levels in ESRD patients are due to the decreased peripheral tissue conversion of T4 intoT3, while thyroid gland production of T3 is normal and T3 clearance rates are normal or decreased, as in other non-thyroidal illnesses.

Conclusion

Thyroid dysfunction is highly prevalent in CKD patients, with the most common abnormalities being low T3 levels and subclinical hypothyroidism, which increase as creatinine clearance declines. While hyperthyroidism is rare in CKD, it can accelerate disease progression. The low T3 state in CKD is not necessarily indicative of hypothyroidism but rather reflects chronic illness and malnutrition, potentially serving a protective role by conserving protein. Treating hypothyroidism in CKD patients can improve renal perfusion, creatinine clearance, and mortality outcomes. Given the overlapping symptoms of CKD and hypothyroidism, routine thyroid function testing is recommended to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment, preventing underdiagnosis and improving patient management.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Being a cross-sectional design, it cannot establish causal relationships between thyroid dysfunction and CKD progression. The use of purposive sampling may introduce selection bias, limiting the generalizability of findings. The sample size, though calculated based on prevalence estimates, remains relatively small, potentially affecting statistical power. Additionally, the exclusion of patients on renal replacement therapy and those with nephrotic-range proteinuria may limit the applicability of results to all CKD populations. Potential confounders, such as nutritional status and inflammatory markers, were not extensively analysed, and reliance on a single-point thyroid function test may not fully capture dynamic changes over time.

Declaration

Conflict of Interest: None

Funding: Nill

AI: AI-based language tools were used solely for grammar and clarity; all interpretations and conclusions are those of the authors.

References

- Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Kausz AT, Levin A, Steffes MW, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 2003;139(2). doi:10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013

- Lv JC, Zhang LX. Prevalence and Disease Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019;1165:3–15. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-8871-2_1

- Basu G, Mohapatra A. Interactions between thyroid disorders and kidney disease. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2012;16(2):204. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.93737

- Khatiwada S, KC R, Gautam S, Lamsal M, Baral N. Thyroid dysfunction and dyslipidemia in chronic kidney disease patients. BMC Endocr Disord 2015;15(1). doi:10.1186/S12902-015-0063-9

- Lo JC, Chertow GM, Go AS, Hsu CY. Increased prevalence of subclinical and clinical hypothyroidism in persons with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2005;67(3):1047–52. doi:10.1111/J.1523-1755.2005.00169.X

- Melmed S, Auchus RJ, Goldfine AB, Koenig R, Rosen CJ, by: Williams RHardinP. Williams textbook of endocrinology. 14th ed. Elsevier; 2019

- Pan B, Du X, Zhang H, Hua X, Wan X, Cao C. Relationships of Chronic Kidney Disease and Thyroid Dysfunction in Non-Dialysis Patients: A Pilot Study. Kidney Blood Press Res 2019;44(2):170–8. doi:10.1159/000499201

- Kang EW, Nam JY, Yoo T-H, Shin SK, Kang S-W, Han D-S, et al. Clinical Implications of Subclinical Hypothyroidism in Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. Am J Nephrol 2008;28(6):908–13. doi:10.1159/000141933

- Carrero JJ, Qureshi AR, Axelsson J, Yilmaz MI, Rehnmark S, Witt MR, et al. Clinical and biochemical implications of low thyroid hormone levels (total and free forms) in euthyroid patients with chronic kidney disease. J Intern Med 2007;262(6):690–701. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2796.2007.01865.X

- Zoccali C, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Cutrupi S, Pizzini P. Low triiodothyronine and survival in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 2006;70(3):523–8. doi:10.1038/SJ.KI.5001566

- Ramirez G, Jubiz W, Gutch CF, Bloomer HA, Siegler R, Kolff WJ. Thyroid abnormalities in renal failure. A study of 53 patients on chronic hemodialysis. Ann Intern Med 1973;79(4):500–4. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-79-4-500

- Lim VS, Fang VS, Katz AI, Refetoff S. Thyroid Dysfunction in Chronic Renal Failure: A Study of the Pituitary-Thyroid Axis and Peripheral Turnover Kinetics of Thyroxine and Triiodothyronine. J Clin Invest 1977;60(3):522–34. doi:10.1172/JCI108804

- Song SH, Kwak IS, Lee DW, Kang YH, Seong EY, Park JS. The prevalence of low triiodothyronine according to the stage of chronic kidney disease in subjects with a normal thyroid-stimulating hormone. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24(5):1534–8. doi:10.1093/NDT/GFN682

- Fan J, Yan P, Wang Y, Shen B, Ding F, Liu Y. Prevalence and Clinical Significance of Low T3 Syndrome in Non-Dialysis Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Med Sci Monit 2016;22:1171–9. doi:10.12659/MSM.895953

- MB S, RT P, DS JM. Serum Calcium and Phosphorous Levels in Thyroid Dysfunction. Indian Journal of Fundamental and Applied Life Sciences 2012;2(2):179–83.

- Kaptein EM. Thyroid Hormone Metabolism and Thyroid Diseases in Chronic Renal Failure. Endocr Rev 1996;17(1):45–63. doi:10.1210/EDRV-17-1-45

- Avasthi G. Study of Thyroid function in patients of chronic renal failure. Indian J Nephrol 2001;11:165–70.

- Rhee CM, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Streja E, Carrero JJ, Ma JZ, Lu JL, et al. The relationship between thyroid function and estimated glomerular filtration rate in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015;30(2):282–7. doi:10.1093/NDT/GFU303

- Joseph L, Desai KB, Mehta H, Mehta MN, Almeida A, Acharya V, et al. Measurement of serum thyrotropin levels using sensitive immunoradiometric assay in patients with chronic renal failure: alterations suggesting an intact pituitary thyroid axis. Thyroidology. 1993 Aug;5(2):35-9.

- Spector DA, Davis PJ, Helderman JH, Bell B, Utiger RD. Thyroid function and metabolic state in chronic renal failure. Ann Intern Med 1976;85(6):724–30. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-85-6-724

- Hardy MJ, Ragbeer SS, Nascimento L. Pituitary-thyroid function in chronic renal failure assessed by a highly sensitive thyrotropin assay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1988;66(1):233–6. doi:10.1210/JCEM-66-1-233

- Gupta U, Jain A, Prakash P, Agrawal P, Kumar R, Farooqui M. To study the prevalence of thyroid disorders in chronic renal disease patients. Journal of Integrative Nephrology and Andrology 2018;5(4):126. doi:10.4103/JINA.JINA_13_18

- Hegedus L, Andersen JR, Poulsen LR, Perrild H, Holm B, Gundtoft E, et al. Thyroid Gland Volume and Serum Concentrations of Thyroid Hormones in Chronic Renal Failure. Nephron 1985;40(2):171–4. doi:10.1159/000183455